Catherine Cooper, The Western Home: Stories for Home on the Range,

Pedlar Press: St John’s, 2014, paper.

Catherine Cooper, White Elephant,

Freehand Books: Calgary, 2016, paper.

Reviewed by Debra Martens

For this 200th post on Canadian Writers Abroad, I have chosen to write about two books that deal with a perennial expat issue: home. Where is home, what is home, why do we long for home? In Catherine Cooper’s The Western Home: Stories for Home on the Range (Pedlar Press 2014), the song “Home on the Range” links the stories, including an essay on the topic. The stories range in time from 1872 to 1988, and in subject, from an alcoholic doctor living in a sod house to a conman son of musicians to a wonderfully awkward father-daughter relationship during an eco-tour. Each story could stand alone, but having that notion of longing for home in the back of one’s mind as one reads, makes the stories stronger, each story itself being “the quest for a home.” While The Western Home is a clever book that impels the reader to use a pencil to track connections, I would like to focus on the novel, White Elephant (which by the way is the name of a bar in one of the stories, “1908, Seeing the Elephant.”)

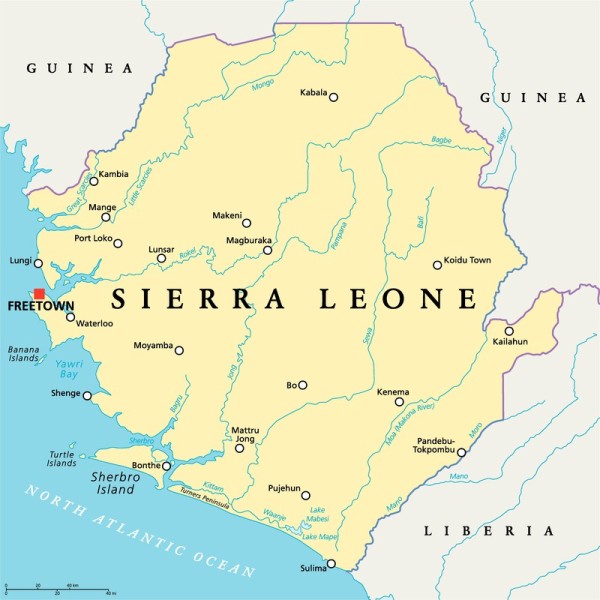

In her novel White Elephant (Freehand Books 2016), Cooper presents the opposite of home as a comfortable safe place. The Berringer family leave a house that they’ve been renovating, at great cost, in Nova Scotia, for a home in Sierra Leone. Richard Berringer always wanted to lead a superior life and chose being a doctor in Africa as the means. His wife Ann has never wanted to be ordinary, and goes with him largely to leave behind the dream home that turned out to have black mold in the walls and to escape neighbourly pity over her husband’s affair. Their 13-year-old son Torquil or Tor is an extraordinarily wilful and contrary child who plays April Fool’s pranks on any day except April 1. He loves his mother (Oedipally) but hates his father for dragging them to Sierra Leone for six months.

The Sierra Leone house provided for them by the Foundation is so monstrous that it is, for Ann, alive, and for Richard, a prison. Each chapter is from the point of view of one of the three, switching throughout. In one of Ann’s sections, the house is “a pulsating mass, a throbbing white body of liberated spores and perpetual oozing” (p. 15). Ann, again: “the Foundation House resembled a pack of animals who, finding themselves surrounded, had huddled together to die. The house itself was like a museum of bad ideas — imported materials not suited to the climate, an oppressive rabbit-warren layout, and no thought given to light or ventilation” (p. 61). In Richard’s section, the house is a fortress: “What few windows there were had heavy bars on them, but no screens, so insects and rodents could come in, but, if there was a fire, the Berringers would have no way out. … The effect of all this was darkness, damp, and the inescapable sensation of being locked in” (p. 85). Tor is more practical in his estimation of the house: “He missed sleeping through the night without worrying about being attacked by biting ants or crawled on by cockroaches” (p. 51). Tor is the one who learns that the original owners wanted the house built close to the river but abandoned it because of the damp (p. 223).

Of course, a home is not made by a building but by the people in it. And these three are all flawed, or well rounded, people. Ann is made out to be hysterical about the mold, despite having an allergy and possibly asthma: she never names it as such, saying instead such things as “her illness” and “…her lungs felt constantly swollen and inflamed” (p. 15). Just as the cobbler’s children go unshod, Richard ignores her allergies that he thinks are all in her head, except for the one time another doctor prescribed her antihistamines and puffers. He never gives her the comforting hugs that she craves. Ann, who also gets malaria (but never complains about mosquitoes) and dysentery, is too sick to give her son the comforts of home that he craves, such as food that he is familiar with. Or such as family traditions: “he wished she could see how much better things could be if you had a few good things that would always be the same, year after year” (p. 101). Richard antagonizes both his son and his hospital colleagues, Ann antagonizes her husband, and Tor starves himself while dreaming up plots to get them back to Nova Scotia. The dog epitomizes their inability to care for each other, oozing from a wound caused by Tor. Ann is a liar, Richard is an adulterer and Tor is a thief and a prankster. Domestic bliss.

Reading White Elephant made me feel anxious for two reasons: Is it okay for a white person to write a book about Africa without including an African’s point of view, but using Africa as a backdrop for a family adventure? Second, is this book meant to be funny?

Cooper subverts most of the items listed sarcastically by Binyavanga Wainaina in his essay, “How to Write About Africa” (Granta 92). The white child is starving, and has running sores, not the Africans. The Berringers have no money and live in poverty, thanks to the expenses of the house and their donations to the hospital (they can’t even pay their taxes!), whereas their neighbours have a TV and delicious food. Yes, there is an old wise man who plays an important role, but the locals consider him crazy and a foreigner because he once lived in America. The white man is not in charge and most of his frustration comes from not being in charge. Indeed, Richard’s desire to help is the turning point of the plot and not in a good way. While the locals believe in the supernatural powers of a child witch, Ann and her friend Maggie are shown as superstitious, selecting bits of Christianity that appeal to them and indulging in exorcism. Cooper leaves it to the reader to decide whether Ann has had food poisoning or driven out demons, whether her swim in the river is merely calming or a rebirth.

Is the story of a white family in Sierra Leone important? I think so. Let me put it another way: if Cooper were writing about a family experiencing culture shock in China, and making bad decisions because of it, would I even be asking this question? I think not. Only because of the legacy left by Joseph Conrad, Graham Greene, and Isak Dinesen (I leave out Margaret Laurence, who did write from the point of view of Ghanaians), and of romantic claims made by the likes of Kuki Gallman, do I ask these questions. And while no chapter is given over to the point of view of a Sierra Leonian, they do hold their own in conversations with the Berringers. Nor is it fair for me to fault a book for what it lacks.

Finally, is White Elephant funny? The Berringer family is ridiculously awful. Perhaps because the story is too close to home (I’m an asthmatic afraid of mold in a foreign place), I felt appalled more than amused as I read. But I wonder. I don’t find the excerpt from the supposedly comedic White Elephant by Julie Langsdorf funny either. Help me out here: is the following funny?

“The first [letter] was from her friend Helen, who had opened a coffee shop in Scotland and was back together with her useless ex-husband. Reading it, Ann enjoyed a guilty kind of satisfaction along with the disappointment she always felt for her friend, who had never even tried to get it right. The next letter was from her sister, who wrote the kind of impersonal brag rags that were really nothing more than long lists of the accomplishments of her painfully ordinary children and gossip about people Ann no longer knew in a place she had spent most of her life trying to forget” (p. 235).

Is Cooper asking us to laugh at Ann, or with Ann, or merely depicting Ann as arrogant? I have struggled with this question while reading this book — is it meant to be funny? or are these just really awful people? — to the point that possession of the novel itself began to feel like my white elephant. And yet, after days of working on this review, I still care about these awful people, still care what happens to them. And I admire the good writing that carries them along — no Amos Ozian metaphorical flights, but prose that marches on in a page turner. I envy the casual way Ann’s character is captured by reading a letter, and I admire Cooper’s offhand “people Ann no longer knew in a place she had spent most of her life trying to forget.” Concisely nasty.

Catherine Cooper is a Canadian author of fiction and non-fiction. The nonfiction aspect of her first book, The Western Home (Pedlar Press, 2014), won the Frederick C Luebke Award for Outstanding Regional Scholarship, and her first novel, White Elephant (Freehand Books, 2017), was a finalist for the Amazon.ca First Novel Award and the Alberta Book Publisher’s Association’s Book of the Year Award. Cooper was born in Scotland and immigrated to Canada when a child. Her family moved frequently throughout her childhood and adolescence, and as an adult she has continued her wanderings both within and outside of Canada. Her work reflects her experience of rootlessness, often focusing on stories of outsiders in cultures or landscapes that are new to them. She is working on a second novel set in the Czech Republic.

Interesting that she chooses that they come from Nova Scotia of all provinces, and go to Sierra Leone of all countries, given the connection between the two.

LikeLike

Interesting, but I do not feel driven to read… and the excerpt provided re. humour did not strike me as “funny”.. still, we need writers describing what it is to move into foreign settings, and our judgments have to be flexible on that account?

LikeLike

Instead of asking if it was funny I should have compared her work to your Kenyan short stories!

LikeLike

Congratulations on your 200th post, Debra!

As always, a wonderfully in-depth review. Responding to your query about the “funny” bits … I can see how a fanatical attention to one’s ailments can strike others as humorous, but I can also see how it can alarm someone who suffers from that ailment/condition. A book’s (or film’s or work of art’s) success depends on the point of view of the reader/viewer, doesn’t it? The film It’s Complicated is a comedy but it’s not funny to someone who is divorced and who pines for their ex-partner.

In White Elephant, Ann reading the brag letter seems to have the same response as most people who are subjected to such letters/emails from time to time; always annoying, like enduring a friend’s vacation photographs. It doesn’t appear that Ann was impressed either, so her reaction strikes me as a normal human response as opposed to arrogant. Funny? Perhaps not. Relatable. Definitely.

LikeLike

Two hundred posts!! This calls for celebration! I wish I could be there to open a bottle of

champagne with you.🍸🍸

These posts have been an exceptional learning experience about Canadian literature and I do hope to

see them gathered together to be published in book form,

a super good thing for CanLit.

LikeLike