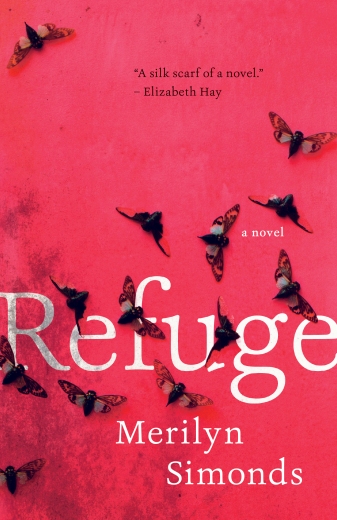

More than one character seeks refuge in Merilyn Simonds’s wonderful novel, Refuge (ECW Press 2018 review copy) — about aging, memory, lies, the stories we tell ourselves and others, and finding refuge.

More than one character seeks refuge in Merilyn Simonds’s wonderful novel, Refuge (ECW Press 2018 review copy) — about aging, memory, lies, the stories we tell ourselves and others, and finding refuge.

Where does Cassandra MacCallum, who hated school, find refuge when she is released from a TB sanatorium back to her family’s diminished farm? In learning to be a nurse. And where does that same girl, now a young woman, find refuge when her thirst for further knowledge is denied by the small-mindedness of her society and time? Mexico. Cassandra then solaces a broken heart in New York City, becoming Sandra O’Brien. She saves her son Charles from the 1934 polio epidemic by sending him back to the farm of her childhood, now a refuge from the world’s troubles (the Depression, the epidemics, the war). This act of seeking refuge from historic events forces the character to take an action that leads inevitably to the next, making links in the chain that pulls each life to its close.

But that is all in the past, a distance delivered by third-person narration. The action of the present, of the first-person narrator, involves Cassandra, as an old woman, and a young refugee from Burma, who claims that she is Cassandra’s great-granddaughter. Cassandra is holed up in her last refuge, the cottage her son built on the island that was once part of the family farm — the same island where Cass hid as a child and where her son in turn hid during his summers in the company of his bitter aunt. Here she is at the age of 96, when 28 year-old Nang Aung Myaing pitches up, claiming that Cassandra’s son, who disappeared at the end of the Second World War, fell out of a plane into the jungle, married, had a child, who then had this young woman. Nang has been denied refugee status by the Canadian authorities and wants Cassandra’s help. But Cassandra is suspicious and wary of opening her withering heart to this young woman’s need.

Merilyn Simonds (photo: Gerry Kingsley)

For how many years Cassandra has been here living on the island is not quite clear — the novel is structured in short pieces that require the reader’s participation to puzzle into a chronological narrative. I tried to pin down the story of Cassandra the way her son and her great granddaughter pin moths flat to a surface. Flip back and forth between the sections out of chronological order, ordered rather the way our memory works, episodes winging their way forward from darkness to light. In terms of structure and imagery, this is a marvel.

The book is divided into four parts, of days, and within those parts are sections (marked by drawings of moths and beetles) that move from the present first-person narrative to flashbacks in the third person. The transition from present to past to present is never abrupt. Instead we segue through time via via an image or sound or object or dream. I took pleasure in tracking the links. For example, in one section Cassandra caught frogs for her father’s Darwinian experiments; the next section begins with the old woman listening to the frogs as she watches Nang approach the cottage: “In the stillness of the morning, the frogs call their dire warnings, their hoarse seductions.

I shake myself from my reverie…” Another example is an action, such as stepping across a threshold. Or by comparison, such as the unadulterated interest of a baby (past) and that of the young man who lives on the farm (present). There are of course more common mnemonics such as photos and music.

Simonds maintains this structure for the first three parts, but in the last section, past and present converge, and there are fewer and briefer flashbacks. Cassandra has worked her way through her various losses, finishing them up by talking to Nang and Sean as she unpacks the boxes that clutter the cottage: her father, her second father Don Arturo, her friend Helen, her lover Carlos, her sister May and her insect-loving son Charles.

Names of insects, insect lore, some science, some history, diseases, weird musical instruments, musicians, artists, photographers, costumes, and a treasure that ruins everything as treasure is wont to do — the novel is itself a treasure trove, presided over by the grand dame who tells lies right to the very end.

A story of an old woman avoiding the present while looking back over her life draws inevitable comparisons with The Stone Angel by Margaret Laurence. Indeed, such a comparison reveals how the novel has changed since 1964. Laurence’s Hagar recalls her past (via objects and photos) in chronological order in much longer stretches of text. A similarity between the two books is that as we reach the climax, there are fewer and shorter flashbacks. Another similarity: both old women eye the breasts of the young. Of a nurse Hagar observes, “her breasts are no bigger than two damson plums”; and Cass observes of Nang, “I can see her little breasts, round and high as suction cups.”

Refuge is bejewelled by fine writing. Here is the child Cass: “She barely knew her letters, but she understood the articulation of bones in their sockets, the cavities that cradle viscera, the placement of lungs and kidneys and heart, the organs of sight, digestion, reproduction, and thought.” And then one day, the child is a teen left alone with her father on the farm: “Her sisters scattered from the farm like leaves blown from a tree…” As her father falls ill with TB, she continues to do what they two have been doing all their lives, observing, noting; she keeps track of his pallor and growing gauntness: “But no amount of forehead-cooling or record-keeping had the least effect.” When Nang comes to visit Cassandra in her lair: “She hesitates, then hunches her pack onto her shoulder and steps across the threshold, ducking slightly, as if stepping into a cave.”

Cassandra’s father tells her, “It’s the will to survive that makes us change.” And change she does, from the child Cass to the nurse Cassandra to the mother Sandra and finally back to her first self, Cass, freshly relaxed, able to observe and learn and open her wings at the age of 96.

Merilyn Simonds divides her time between Canada and Mexico. Read more about her and her work here: Merilyn Simonds.

Reviewer Debra Martens divides her time between Jerusalem and Canada.

Thank you for such a thoughtful review—and for the moth!

LikeLike

An excellent review. Sounds like a must read!

LikeLike