Earle Birney is perhaps best remembered for his poems “David” and “Bushed,” which were mandatory reading in schools for a time. Birney was a poet, novelist, professor — and soldier.

Earle Birney wrote twice about Nijmegen, a town in Holland where the Canadians were in 1944-45. Access to it was by a highway called the Maple Leaf.

Earle Birney wrote twice about Nijmegen, a town in Holland where the Canadians were in 1944-45. Access to it was by a highway called the Maple Leaf.

What I find interesting is comparing his poem, “The Road to Nijmegen,” to what he wrote about the place in his comic novel Turvey: A Military Picaresque, originally published in 1949. (I’ve read the New Canadian Library 1976 digital reprint 2008, with an Afterword by Al Purdy. And why does a digital book restart pagination with each chapter?) Most of Thomas Leadbeater Turvey’s two years following his enlistment were spent either in delays by a psychiatric misdiagnosis, in various punishments or in hospital: the punishments arising indirectly from the consumption of too much beer, and the hospital for a broken ankle, dysentery, and when he finally made it to the front, diptheria. None of which deterred his lust for life.

In Turvey, Birney tried on the many accents of the front, pronunciations that often left his hero bewildered and at times his reader fatigued. (His hospital roommate, for example, says of his procedure, “Tabernacle, dat worse dan a mortar bumb.”) But when we get to Nijmegen with Turvey, the text is straight-up description. Approaching the front, Turvey’s excitement is evident: “Headed for the front! For the Sharp End! Well, for Nijmegen anyway, which everyone said was within shell range, almost at the very tip of the Canadian salient, in danger of being nipped off any time.” Within a few sentences his enthusiasm deflates: “Turvey wasn’t nearly as happy as he thought he would be… Perhaps it was the chill January day and the bleak sights along the highway.”

Troopers of a Canadian armoured brigade getting out of an armoured truck near Nijmegen, Netherlands, December 5, 1944. Credit: Lieut. Barney J. Gloster / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-177591 Mikan 3262645

What were these bleak sights? “Then the Maple Leaf Up ran straight for miles between a boulevard of ground-level stumps, all that was left of lombard avenues cut for road-blocks or fuel or mine-props. Through the raw mists swirling across from the colourless fields Turvey could see ragged old men and shawled women silently carving chips from some of the stumps with long butcher knives, and stowing the frosty fragments carefully into straw baskets and pails. The road swung and narrowed into cobblestone. They bumped through a dead village, fiercely killed in some artillery or aerial duel, a shapeless collection of rubble through which chimneys reared like broken old teeth.” There are ruined trucks and tanks littering the sides of the road as well as working ones travelling down it. Turvey’s description is entirely in the moment and he has no thoughts for his lover in England or even his constant thirst. He sees children on the bombed road “fingering the heaps for nuggets of tar or burnable flakes of asphalt, and stowing their loot in shopping bags.” He concludes, “No, Turvey somehow could not fall into gaiety on the road to Nijmegen as the mist thickened to rain and then to sleet. But he took out his tonette and played “Clementine” to himself…”

The poem, however, is told in the first person, not third, and is addressed to “you.” “The Road to Nijmegen” opens with the narrator thinking of “your face” en route. He thinks of “my dear” as he passes “bones of tanks beside the stoven bridges/ and old men in the mist/ hacking the last chips/from a boulevard of stumps.” There are women on bicycles, and again the children, this time “groping in gravel for knobs of coal.” He is numb with cold: (Birney’s footnote to the poem describes the winter as “one of the coldest of the century” and the land “denuded of trees, coal and foodstocks by the retreating Germans.”) The difference between the poem and the descriptions of the novel and the footnote comes in the last stanza below, where the narrator draws a larger picture to raise ethical questions. Whether by the comic exaggeration of the novel or the serious tone of the poem, Birney’s message is the same: let us remember the war in order to keep peace and to have a future.

So peering through sleet as we neared Nijmegen

I glimpsed the rainbow arch of your eyes

Over the clank of the jeep

your quick grave laughter

outrising at last the rockets

brought me what spells I repeat

as I travel this road

that arrives at no future

and what creed I can bring

to our daily crimes

to this guilt

in the griefs of the old

and the graves of the young—Earle Birney, from “The Road to Nijmegen” in The Collected Poems of Earle Birney Vol. I (McClelland and Stewart 1975), pages 86-87.

Trucks loaded with refugees and their bicycles, who were evacuated from south of Arnhem, arriving at Nijmegen, Netherlands, 20 November 1944. Credit: Capt. Frank L. Dubervill / Library and Archives Canada

Earle Birney (1904-1995) was a personnel selection officer in the Second World War. Birney grew up in Alberta and B.C., studied in Toronto and Berkeley. He did a Ph.D. in Chaucer studies with the University of Toronto in 1936, having lived in London to study at the British Library from 1934 on a Royal Society fellowship. His collection David and Other Poems was published in 1942, the same year that he enlisted, and it won the Governor General’s Literary Award. Turvey, published in 1949, won the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour. After his retirement from the University of British Columbia’s English Department in 1965, he lived in France, England, and Mexico for a time. From the 1960s onward, Birney became known for his travel or world poetry, exploring locales from Spain to India.

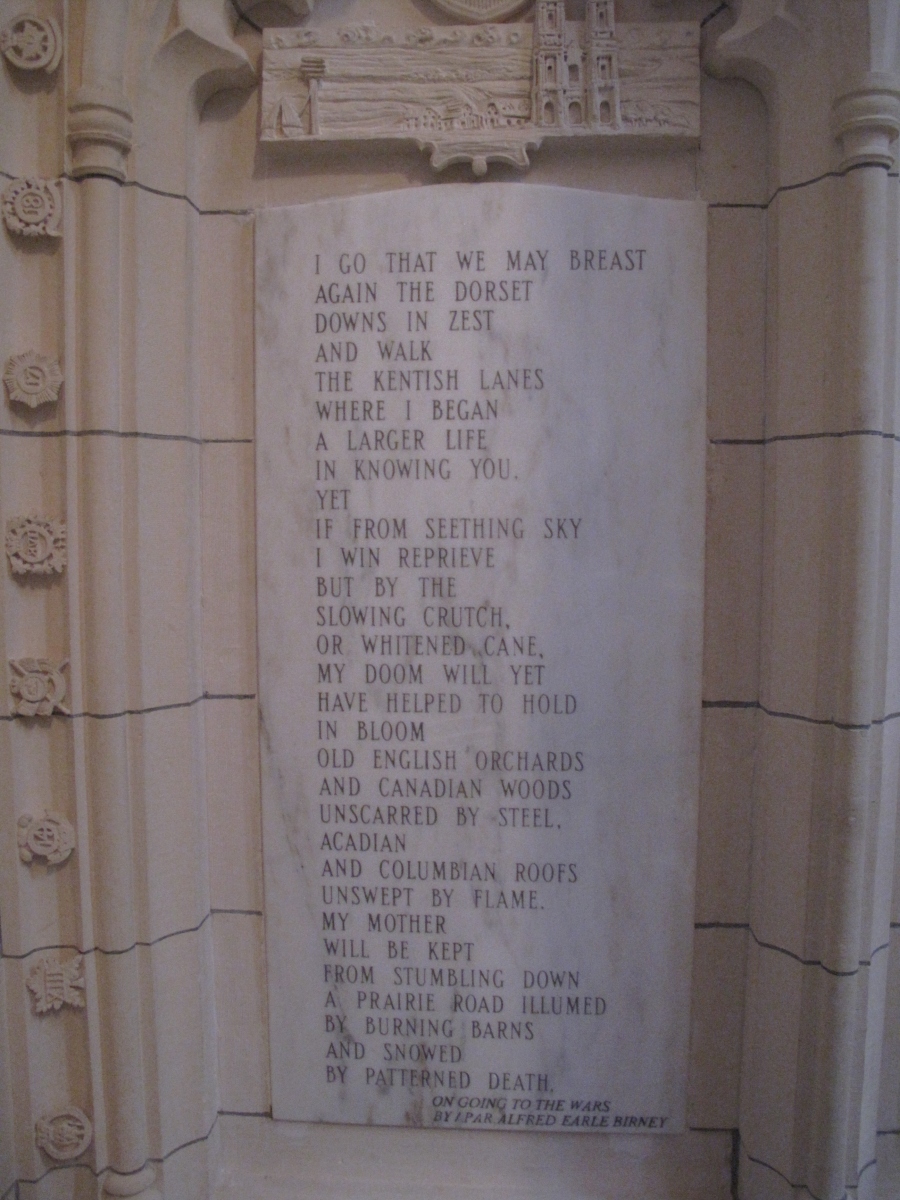

“On Going to the Wars” by Earle Birney, from the Memorial Room in the Peace Tower, Ottawa, Canada. By Kurtrik – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64034389

Related Links

- Featured image at top: Personnel of the 4th Canadian Reinforcement Battalion (Canadian Army Miscellaneous Units) boarding a train en route to England, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 1 June 1945.Credit: Capt. J. Ernest DeGuire / Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-168486

Mikan:3230277

- Here is a link to a photo of a younger Birney, Museum and Archives Bowen Island British Columbia.

- Review of Turvey, “A long, long way from Skookum Falls: Turvey by Earle Birney.”

- Canus Humorous.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia entry on Earle Birney needs work — the photos disappear.

Lovely. I’ve just recently reread some of the classic Birney poems (and Purdy and Pratt) so I enjoyed this reminder that Birney wrote quite a lot besides the oft-assigned “David”. And fiction, too! I think Elspeth Cameron has written a biography of him; I should really have a look. With Turvey too, of course.

LikeLike

Thanks! Yes, they are worth another reading.

LikeLike

Thanks for this interesting, thoughtful article. So apt for November 11 and a refreshing change from some of the stock phrases and sentiments often served up on this day. On Remembrance Day the words “sacrifice” and “duty” pepper the formal speeches, while some people are content to just dismiss the commemorations with stock phrases of their own about militarism. This remembrance of Birney’s work gives us deeper insights. I learned a lot. Haven’t read Birney since high school. I had no idea about this early novel. Fascinating.

LikeLike

Yes he lived a long and productive life. I was surprised to see he had a poem in Parliament.

LikeLike