Review of Modernist Voyages: Colonial Women Writers in London, 1890-1945 by Anna Snaith, Cambridge University Press 2014, 278 pp hardcover

(ISBN: 9780521515450). Reviewed by Debra Martens.

Modernism is loosely defined as the period between the Victorian and the Second World War – a broad category into which you could shoehorn almost any work that shows signs of rebelling against its predecessors. Indeed, the colonial women writers who are the subject of Modernist Voyages span the period: Olive Schreiner (1855-1920 from South Africa), Sarojini Naidu (nee Chattopadhyay, 1879-1949, India), Sara Jeannette Duncan (1861-1922), Katherine Mansfield (1888-1923, New Zealand), Jean Rhys (1890-1979, Dominica), Una Marson (1905-1965, Jamaica), Christina Stead (1902-1983, Australia), and in the Afterword, Elizabeth Smart (1913-1986). The gaps between them, such as the 26 years between Marson’s London arrival and Sara Jeannette Duncan’s 1906-1907 stay, or Stead’s arrival six years after Duncan’s death, are not a problem if you view this book as a collection of disparate essays on women writers who happened to come from the colonies to live in England. In fact, Anna Snaith offers the disclaimer that her book is not exhaustive but presents case studies (p. 17). Rather than a chain with which to bind these writers together, modernism is more a comfy bed.

Anna Snaith (King’s College London, BA from University of Toronto and PhD from University College London) does, however, pursue several themes throughout the book. In her introduction she ticks off the ‘isms’: “The combined focus on urbanism, capitalism and colonialism in their work constitutes a thoroughgoing consideration of the forms of modernity and its transnational manifestations.”(8) She also discusses feminism, racism and articulations of identity and gender. For the general reader I recommend skipping the introduction for the more comprehensible individual chapters.

Given how little we know about Sara Jeannette Duncan’s life, I was excited to discover her contemporaries. We find out, for example, that Olive Schreiner started off in England studying nursing and interviewed prostitutes for her novel From Man to Man. We learn that poet and politician Sarojini Naidu first came as a teen student and was influenced by Edmund Gosse, Arthur Symons, and W.B. Yeats via the Rhymers’ Club. She went to Browning Society meetings and was interested in Irish Home Rule for its parallels to Indian Home Rule.

Katherine Mansfield also came to study and started her writing career in periodicals (after a marriage, a miscarriage, and contracting both gonorrhoea and TB). Her work appeared in The New Age and then Rhythm, which she co-edited and funded. According to Snaith, Jean Rhys arrived in 1907 to study drama but was forced by her father’s death into work as a chorus girl. Uma Marson’s experience 25 years later saw her become the head of the West Indies Service for BBC, and later founder of BBC’s “Caribbean Voices” (1945-1946). While both Rhys and Marson encountered racism, Marson’s more positive experience of London suggests the difference a quarter century makes. About these writers we learn such things as what they did, who they saw, and what institutions they belonged to. I should add that there is no suggestion of them having met each other or even known about each other.

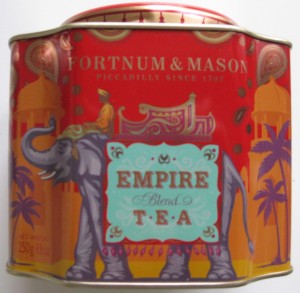

We are given some of this background about Sara Jeannette Duncan in Chapter 3. Duncan was a member of the Ladies Empire Club in Grosvenor Street – but we knew that already from Marion Fowler’s biography, Redney. Duncan’s characters in Cousin Cinderella visit the Royal Colonial Institute off Trafalgar Square. Snaith points out that single women were attracted to Bloomsbury for the rooming houses and to Kensington for the apartments in mansion blocks. The flat Duncan stayed in at Iverna Court was new (106-107). We are reminded of her friendly relations with James Louis Garvin, editor of Outlook and Observer. Snaith mentions that Pauline Johnson, Duncan’s school friend, came to London to perform in 1906 and 1907, when Duncan was there – but there’s no mention of whether they met (104).

And that is all we learn about Duncan’s English life and literary influences. I had hoped to learn whether Duncan’s work changed after E. M. Forster visited her in India, for example. Or what caused her to switch from fiction to plays during WWI? What did she read and who did she talk to during her solitary years in London?

Instead Snaith gives us a close reading of Duncan’s 1908 novel, Cousin Cinderella, with reference to The Imperialist, providing background on imperialism, tariff reform, eugenics, and um spatial politics. Cousin Cinderella is about Mary (first person narrator) and her brother Graham Trent, who are the children of a wealthy Canadian lumber baron who sends them to England as “samples” or “editions”, to both show the success of the colony and to be further refined by the mother country. Mary’s tone is light, arch, as she mocks English ignorance of Canada – it is her first-person critical voice that makes the novel modern (109). She is offended by English snobbery and by her relegation to the sidelines as Graham is pursued as an eligible match and invited to all manner of political meetings and lunches. Evelyn Dicey, their American friend, also rich, introduces Mary and Graham to high society, particularly to the Duke and Duchess of Dulwich and Lady Doleford with her two marriageable children, Barbara and Peter.

The Duchess of Dulwich does not come off well in Mary’s eyes, perhaps because she calls her “Miss Canada.” She is made to say such things as “I am not very fond of aliens,” although she is involved in the Royal Commission into the Assimilation of Aliens (following the Aliens Act of 1905 which meant to stem the flow of Jewish immigration from the pogroms in Russia and Poland) (102). The Duchess encourages marriage of “daughters of our own kith and kin beyond the seas” (colonial women) to the English, explaining, “And if such ideas seem in any way sordid or grasping, it should be remembered that the Colonies pay nothing, for the protection afforded them by the British navy.” (101) From this silliness Snaith concludes: “Colonial women are to be offered in marriage as repayment for military protection and security” (101), overlooking that it is the Duchess who says it and not Duncan or Mary. The idea of eugenics is discussed because both the Duchess and the Trents mention the English would be rejuvenated by marriage to healthier colonials. Mary surprises everyone by falling in love with Peter (supposedly matched to Evelyn); by novel’s end they are engaged.

No, wait, according to Snaith this marriage has nothing to do with Mary’s desires or the increased beating of her heart in Peter’s presence. She is merely realizing her capital, her commodification. “Mary sacrifices herself through marriage to preserve the freedoms and needs of the male nation-builder” (101). Lost me there. And again, “By highlighting Mary’s position as a product, Duncan points out the limitations of women’s role in imperial relations.” (109) The passages Snaith quotes in support of her assertion seem to me to be about feeling one’s potential in the anonymity of a city (“the definite thrill of a new perception, something captivating and delicious”) (100) and about Mary’s awareness that everyday details, however sweet, would be swept away in the telling of tales from high society (109). The plot twist that Mary gets Peter, that Graham is thrown over by Barbara, and that Evelyn marries Peter’s uncle, suggests that Duncan was toying with both the reader’s and the Duchess’s expectations.

Anna Snaith’s reading brings to our attention that Duncan, whose career began in journalism, not only was aware of the political issues of her day but also incorporated them into a comic novel that sold well. By the end of the chapter I can accept Snaith’s conclusion that Duncan was “writing against an empire in which both Canada and women have a subservient role.”(109).

What to make of the writers, or these “colonial modernists” (205), as a whole? Snaith: “The articulation of national or colonial identity, then, is a dynamic process; it does not arrive intact, but is constructed in partial response to reception and is the result of a continual process of reinvention.” (20) Which means, I think, that the lives and works of the writers above confirm the idea that you can reinvent yourself in a new place, and the place in turn reshapes you.

Related

Anna Snaith also wrote Virginia Woolf: Public and Private Negotiations (2000). She edited Virginia Woolf’s The Years for Cambridge University Press Edition of the Works of Virginia Woolf (2012), edited Palgrave Advances in Virginia Woolf Studies (2007) and co-edited Locating Woolf: The Politics of Space and Place (with Michael Whitworth, 2007).

Snaith’s Modernist Voyages is reviewed by Peter Murray in Twentieth-Century Literature (Duke University Press).

[…] Now why, you might ask, would I hie me thither to look at portraits of rich American women, be they titled or no? Because of Sara Jeannette Duncan’s fascination with wealthy American women in at least two of her novels, Cousin Cinderella and the earlier An American Girl in London, and because of the references to these American types in the recently reviewed Modernist Voyages. […]

LikeLike

Barb and I really like how you translate academic speak into plain language. No mean feat!

LikeLike

Thanks. It was a challenge.

LikeLike