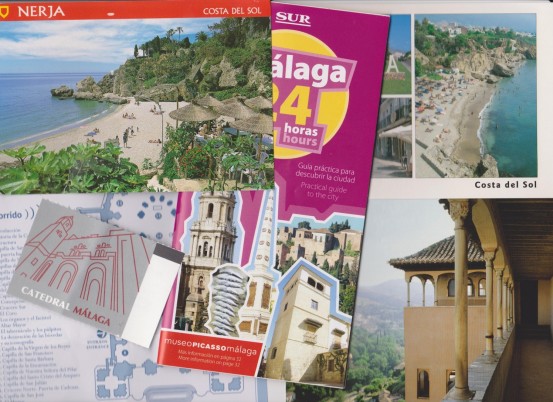

White. White stones on the beach, white buildings, white stones in the paving of streets, white marble steps with flat red brick edging. Olive trees hiking up the hills, agriculture crammed onto the terraces. A ribbon of road squeezed between coast and hills. You’d think I’d write about the blue of the water beside our hotel near Nerja in Spain at the end of February. But I was struck by the white of things. Perhaps this had something to do with coming from the land of grey. When I lived in Kenya and India, I couldn’t understand why so many northern Europeans came for one week to such farflung places. After a year and a half under grey skies, I now understand the draw of the sun.

Over lunch one day, in either Málaga or Grenada, the hills and caves visible from the road got me to thinking about the Spanish Civil War and whether Norman Bethune had come this far south. Can it be that you don’t know who Norman Bethune is? He was a Canadian doctor who went to Spain in 1936 to join the International Brigade to fight the fascists, and who created the portable transfusion clinic. He also went to China, where he was welcomed for his innovative treatment of TB and for his hospital field work there too during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Much admired in China, he was brought to the attention of Canadians by the book The Scalpel, the Sword: the Story of Doctor Norman Bethune (1952), by Ted Allan and Sydney Gordon.

Given that several Canadian writers have been to Spain, this is not the place to write about my family vacation nor about a revolutionary doctor, even if he was Canadian – unless I can work in some literary connections. How many can I make?

One of the biographers, Ted Allan, wrote a novel about his time in Spain with the International Brigade, called This Time a Better Earth (1939). Never heard of it? Then perhaps you have heard of Love is a Long Shot (1984), which won the Stephen Leacock Award. Or his short story and screenplay, Lies My Father Told Me.

While The Scalpel, the Sword is inspiring, I was irritated by the present-tense scenes that read like a film script. My irritation is nothing compared to the criticism of others, from the Canadian Encyclopedia’s mention of lack of documentation to the Globe and Mail’s reviewer: “Though it moved many readers, the book was an unreliable hagiography stuffed with invented dialogue and lacking footnotes, an index or any other scholarly apparatus. More than half the book was set in China, where the two authors had not set foot. They drew liberally on a 1948 Chinese novel by Zhou Erfu, Doctor Norman Bethune, which they forgot to acknowledge.” -Judy Stoffman, Globe and Mail, 19 May 2009.

The book Stoffman was reviewing was not The Scalpel, the Sword but a biography of Norman Bethune by Adrienne Clarkson, one of the Penguin Extraordinary Canadians series, titled, simply, Norman Bethune. The former Governor General has published, among her many works, the novel: A Lover More Condoling (1968), about a Canadian widow in France. There are now several works about Bethune’s life, including the 2011 Phoenix: The Life of Norman Bethune by Roderick and Sharon Stewart.

I wondered if the fighting in the Spanish Civil War had brought Bethune south.

English: Canadian Blood Transfusion Unit which operated during the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Norman Bethune is at the right. ca. 1936 – 1937 / Spain Italiano: Unità transfusionale canadese durante la Guerra civile spagnola. A destra il dott. Norman Bethune. ca. 1936 – 1938 / Spagna (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

Indeed it had. Allan and Gordon include a long excerpt from Bethune’s journal about taking a medical van south along the coast and coming to a halt because of the wave of refugees from Málaga, which had fallen to the fascists. Bethune describes how they empty the truck of its medical supplies and ferry first children and then families to Almeria, and he writes of the bombing of those refugees gathered in the main square of Almeria. Bethune later revised his journal for publication as a pamphlet by the government as Málaga – the Crime on the Road. Here is an excerpt from Bethune’s journal of his four days on the Almeria – Málaga road:

Words- — bah! Everywhere a deluge of fat words, and under the deluge, here on the Málaga road, the lost and the damned. If only I had a thousand pairs of hands, and in each hand a thousand deadly guns, and for each gun a thousand bullets, and each bullet marked for an assigned child-killer – then I would know how to speak! (p. 145)

What caused such anger? To understand, you have only to read his description of having to choose who goes in the truck to safety and who stays behind for the fascists, of their desperate plucking at his clothes, calling to him. Here is his description of a night on the road, where the truck can go no further:

A great silence settled over the refugees. The starving lay in the fields, gripped by torpor, stirring themselves only to nibble at fugitive weeds. The thirsty sat on the rocks, trembling, or staggered about aimlessly, the wild glassy stare of delusion in their eyes. The dead lay indiscriminately among the sick, looking unblinkingly into the sun. Then the planes swept overhead – glinting, silvery Italian fighters and squadrons of German Heinkels. They dived toward the road, as casually as at target-practice, their machine guns weaving intricate geometric patterns about the fleeing refugees…. (p. 150)

The best parts of The Scalpel, the Sword are the excerpts from Bethune’s letters and journal. Fortunately, I am not the only admirer of Bethune’s writing. Larry Hannant edited and published a collection of Bethune’s work in 1998 as The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune’s Writing and Art (U. of Toronto Press).

Ok, you laid-off journalists, which one of you is going to write the biography of a maverick Canadian doctor working on the front somewhere with Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders?

Related articles

- Ted Allan on Norman Bethune (CBC)

- Ted Allan’s son on Ted Allan

- L’Actualité on Bethune (actualite.com)

Back in my highschool days I was part of a school trip to Malaga and we also spent time in Nerja. I really had no idea what the history of the area was ( we were more into the disco mindset!) and even as an adult I didn’t realize what went on there and the role of Bethune. Forty years later, my eyes are opened.

LikeLike

The Jerome Martell character in The Watch that Ends the Night seems to be inspired by Bethune, though Hugh MacLennan always denied it.

LikeLike

Very interesting piece. And what a worthwhile way to spend some of your holiday time — reflecting upon and writing about Bethune’s role in the Spanish Civil War — rather than just vegetating on the beach. I was deeply moved by his passionate quotes. I also couldn’t help but think about Bethune’s early hero worship of Mao and Mao’s subsequent brutal excesses.

Gabriella

LikeLike

Interestingly, I commissioned reviews for CMAJ of two recent biographies mentioned in Debra’s blog.

The first looked at Clarkson’s effort, which appears to have been a bit on the Pollyanna side.

http://www.cmaj.ca/content/180/13/1334.full.pdf+html?sid=bfd50cf3-0b4e-43a4-a124-a369f0124b17

In contrast, the Phoenix book by the Stewarts was more reality-based. “According to Stewart and Stewart, Bethune was a communist, a scoundrel, an alcoholic, a womanizer and perhaps a reckless surgeon. Yet he was a visionary, a humanitarian and a champion of the suffering.”

http://www.cmaj.ca/content/184/5/566.full.pdf+html?sid=006c577b-5b73-4a73-889e-3a97ca59f88b

He sounds like he’d make a great dinner companion… but not a wholly trustworthy friend.

Cheers, Barbara

LikeLike